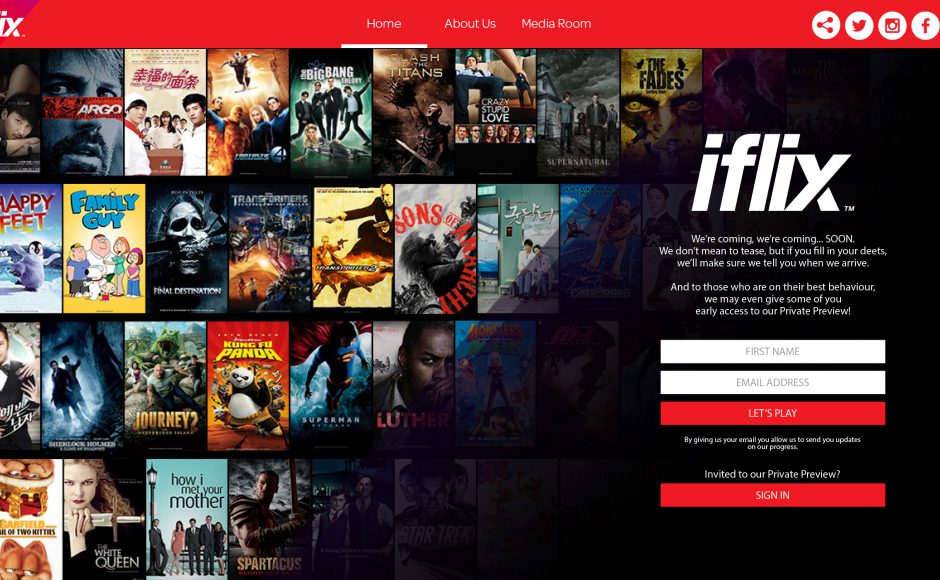

Britt says iflix has solved the problem of how to execute a business with world-class standards and local execution. Source: iflix

Going native: iflix’s Mark Britt on why company keeps everything local

Once you’ve spoken long enough to Mark Britt – co-founder and CEO of iflix – Asia’s purported answer to the Netflix age—there is a sense the cultural zeitgeist of the world is undergoing a significant sea change, with the nexus of that change coming from the world’s emerging markets.

In the years since the Internet revolutionized the way we consume content, cultural norms are still largely dictated by English-language, Anglo-Saxon perspectives. It’s that precise monopoly iflix is seeking to break by introducing the flavors and textures of individual markets into their subscription service, in the hopes of capitalizing on a thirst for local execution and representation.

LIVE from Wild Digital: put yer hands together for the one & only Mark Britt! pic.twitter.com/uOViug60el

— iflix Malaysia (@iflixMY) June 8, 2016

iflix was founded by the Catcha Group back in 2015 and after a few years, the Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD) service has emerged as one of the leading players in online entertainment content in Southeast Asia. The service is currently available in 18 countries across Asia, the Middle East and Africa, with plans by the company to spread its particular cocktail of local and international offerings further and further afield.

At the Catcha Group’s annual Wild Digital conference held recently in Kuala Lumpur, Tech Wire Asia had the opportunity to speak to Britt about the company’s decidedly local take on things, and why global companies just don’t seem to get emerging markets.

iflix has had to field tonnes of comparisons to well-known Netflix, but Britt has insisted his company’s goal is not to serve as a counterweight to the American SVOD service but rather as a service with emerging markets on its mind. And the company is approaching this from all fronts – whether it’s by assessing the limits of a country’s Internet infrastructure, available payment mechanisms, or even the very pricing strategies they implement.

SEE ALSO: Southeast Asia’s SVOD scene hotbed for competition and growth

“I think the problem iflix has solved has been how to execute a business with world-class standards and local execution,” he said.

“Once we realized we had to think differently about [each country], and put in place the business processes and the capabilities to execute locally, we’re quite comfortable whether it’s Sudan or Iraq or Kuwait or Thailand, because we have a business model that allows us to take a bottoms-up, local approach and customize further into local payment mechanisms, pricing, telco bundles and infrastructure to make it easy to buy.”

Britt and his partner, Patrick Grove, founded iflix in order to bring quality content to emerging markets. Source: iflix

Although Netflix sells their subscription packages for lower rates in emerging markets compared to North American prices, iflix’s cheap memberships keep the service competitive, and also displays a real awareness about the lifestyles of those living this side of the world. The same goes for its highly localized and culturally-aware content library.

“The markets we’re passionate about are the ones that large companies traditionally don’t care about,” Britt said.

“I think the recipe for success is not high priced premium products. It’s mass-market, low-cost high volume, where you can create an enormous amount of value.”

From our conversation, one surmises that for Britt, the technology of the future is in a constant discourse with monopolies of every sort, whether it’s Netflix’s brand prominence in the streaming industry, or the not-inconsiderable influence paid television models still wield over entertainment content. This might be especially true in markets like Malaysia, where brands such as Astro retain 60 percent profit margins, and where customers are still largely subject to both subscription fees and advertising.

“You’re reaching an enormous amount of people who historically have not had access to content because they couldn’t afford paid TV,” he said.

For Britt, the act of creating services that are culturally aware of their place in the world is itself a radical act of disruption, perhaps even of social justice, even though the company is definitely focused on its commercial bottom line.

iflix also broke with convention when they recognized that the problems international players were grappling with weren’t necessarily their own – a kind of opinion monopoly, one might say. For consumers in emerging markets, the cost of paid television and the lack of proper infrastructure were the true obstacles in the company’s way.

“Before you can even think about content, that’s the actual use-case scenario you’ve got to solve for.” – Britt

“It’s actually funny to see the large global players in a competitive battle to get to 4K and HD video,” he said. “But all of iflix’s work is [figuring out how to] get 172kbps of video working on a 3G connection, and working to bundle it with an off-peak data plan.”

An amnesiac Grim Reaper, the faithful servant, and one cursed Goblin on the lookout for a human bride. Watch all episodes of #GoblinOniflix! pic.twitter.com/jWYdF0ayKM

— iflix Philippines (@iflixph) June 15, 2017

The true magic of iflix has been its ability to perceive their audiences in emerging markets as culturally complex and textured locales. The company has made its name by introducing a highly market-specific content libraries meticulously curated to address both the local tastes and more unusual, but popular, flavors.

For instance, Indonesia has seen a burgeoning preference for South Korean dramas, a relatively new phenomenon iflix has capitalized on by introducing a back catalogue of popular shows. On the other hand, animes like the successful Attack on Titan, which would otherwise have been ignored by Malaysian players such as Media Prima, found a passionate digital audience via the platform.

“There are entire segments and categories like horror that have not been traditionally well-served but have very passionate digital audiences,” Britt said.

“The challenge paid television and free-to-air do not do particularly well is they do not allow you to find more of what you are passionate about, and that’s the beauty of digital. It puts you in control to go find more of what you love.”

Britt and his team broke not only the monopoly paid-TV operators had over what content got distributed, but also what kind of content got air time. He also noted the localization problem was largely a product of fortunate happenstance. The founders had always known their libraries would have to be more diverse, but they “massively underestimated” how much non-English content could scale.

“What we quickly discovered is that the scale of the market for English-speaking content is actually quite small in most emerging markets,” he said.

SEE ALSO: Netflix confirms deal with Baidu-backed iQiyi in China breakthrough

Rather, by considering factors such as subtitles and sensitive content, the company was able to capitalize on a thirst for entertainment that accurately reflected each audience’s cultural norms. That goes not only for the lingua franca of any one market, but also the censorship standards imposed by each country.

“Two things are simultaneously true: the Internet is a wonderful liberalizing force for human rights and free speech and democracy, but communities and governments must also have a right to set their own community standards,” Britt said.

“In a media company, if you start with that perspective it’s a much more constructive conversation than if you’re a global business who… has an expectation all the world should follow your cultural standards.”

The global cultural hegemony, rooted in Anglo-Saxon perspectives, is another kind of monopoly that companies like iflix are seeking to break.

Western companies have experienced a bitter backlash in Asia, particularly technology companies such as Amazon and Uber that have been rebuffed by local players such as Lazada and Grab, while huge companies such as Paytm and Alibaba continue to dominate China and India. WebTV Asia’s Group CEO Fred Chong said at the recent Echelon Malaysia conference that “arrogant” international creators who merely import their products with very little change have never taken the time to understand the markets they seek to penetrate.

Britt agreed with his assessment: “I think there is a deep desire in customers in every country to feel well understood, and the challenge is when you look at the world through a single footprint, and treat it all as one country, it’s difficult to emotionally connect with customers from a brand point of view. That level of customer empathy is a really important part of what the Internet is about, and I don’t think global companies get that.”

“That media is a fundamentally local business—packaging, tastes, curation. The cultural calendar is very different, and the local zeitgeist is very different market to market.”

Britt sees the fresh innovations emerging from economies such as Korea and China, as well as from startups like Indonesian Go-Jek, as central to the success of emerging markets today.

As the cultural tides of the world continue to shift away from Western hands, it’s ever more imperative that consumers “feel there is a local execution of the product” as “it builds a much greater brand affinity and understanding.”

READ MORE

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach

- Insurance everywhere all at once: the digital transformation of the APAC insurance industry

- Google parent Alphabet eyes HubSpot: A potential acquisition shaping the future of CRM