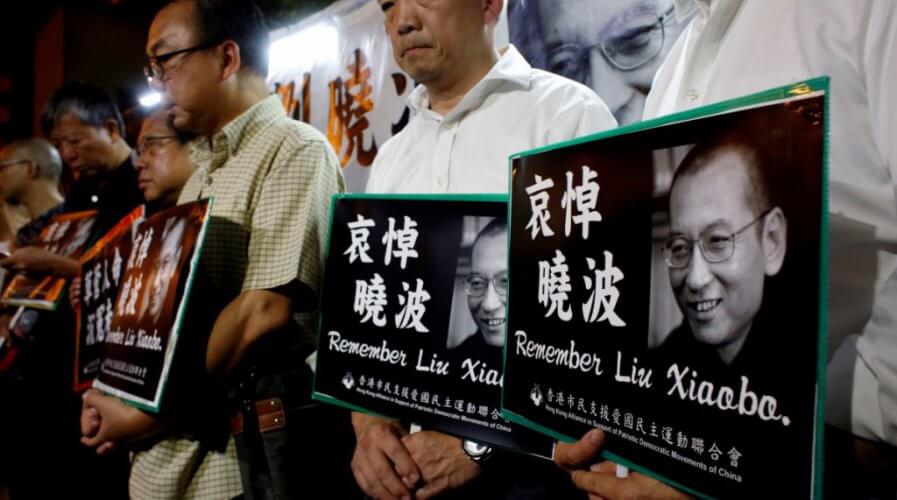

The death of Liu Xiaobo was all but eliminated on Chinese media. Source: Reuters

Death of Liu Xiaobo highlights power of China’s censorship machine

THE DEATH of Liu Xiaobo, prominent Chinese political dissident and Nobel Peace Prize winner, has had the unintentional side effect of giving the world a view into China’s remarkable censorship powers, spanning information technologies from social media to broadcast television.

As the world mourns the death of one of China’s most famous political prisoners, you’d be hard-pressed to find any real mention of Liu Xiaobo or his passing anywhere in the Chinese media landscape.

This is hardly surprising. Foreign China watchers and journalists have noted China’s formidable media censors have started working on wiping any memory of Liu from the technosphere.

Tencent WeChat is censoring Liu Xiaobo related content for mainland users only. I assume that's the technology China wants FB to adopt. pic.twitter.com/9khw0KbgQi

— Wei Du 杜唯 (@WeiDuCNA) July 14, 2017

Web searches in China have yielded very little information about Liu and his death. A BBC report noted searches of Liu’s name in China’s search engine, Baidu, yielded only a February-dated article. Meanwhile, searches in popular microblogging site, Sina Weibo, bring up an eerie message: “according to relevant laws and policies, results for ‘Liu Xiaobo’ cannot be displayed”.

The media blackout on Liu is a result of the dissident’s outsized role in protesting the Communist Party’s cover-up of the Tiananmen Square massacre, an incident that remains a historical blind spot for many in China. After the massacre, Liu began agitating for an overhaul of China’s policy of one-party rule, actions which earned him an 11-year jail sentence. He has been jailed since 2008.

SEE ALSO: Thailand asked Google to make censorship easier – leaked document

Since his death, media outlets in China have been careful to sidestep the issue of his detainment and death. The BBC reports broadcasters Xinhua and CCTV released only brief statements, while the Global Times called him “a victim led astray” by Western powers.

“The Chinese side has been focusing on Liu’s treatment, but some Western forces are always attempting to steer the issue in a political direction, hyping the treatment as a ‘human rights’ issue,” it wrote.

Other domestic outlets have largely ignored the news altogether, though that doesn’t mean foreign media companies have been left unscathed. The BBC’s China correspondent posted a video on Twitter depicting a broadcast being cut short by a literal blackout of the television screen.

NorwegianNobelCommittee said "the Chinese Government bears a heavy responsibility" for LiuXioabo's death: BBC screens go black across #China pic.twitter.com/z6kDnJrMX0

— Stephen McDonell (@StephenMcDonell) July 13, 2017

Social media has not fared much better either: Tech in Asia reports numerous posts on Weibo featuring a candle emoji have been deleted, or attempts to post have returned “permission denied” errors. Candle emojis on Weibo have been used in the past to commemorate the passing of someone, and there are clearly forces in Beijing’s censorship machine determined to burn Liu from his home country’s collective memory.

Tencent’s WeChat app has reportedly removed any mention of Liu-related content for mainland users, according to Channel News Asia‘s China correspondent, Wei Du.

SEE ALSO: Baby, it’s cold outside: Facebook builds censorship tool to attain China re-entry

“Weibo is really busy tonight – things are constantly being deleted. Even R…I…P is being deleted,” wrote Weibo user TobyeandElias, noting how social media users cannot even associate the concept of mourning with Liu. The user might also be giving voice to what many are now witnessing as the long arm of China’s censorship powers.

“Weibo is really busy tonight – things are constantly being deleted. Even R…I…P is being deleted,” wrote Weibo user ‘TobyeandElias. Source: BBC/Sina Weibo

Reams of work and millions of words have been devoted to China’s restrictive media landscape, many parties largely let it all pass because of the country’s outsized political and economic influence.

The media blackout on Liu should give us pause, especially those of us seeking to work with China as they grow in stature. A country’s government has the right to shape its direction, but the chokehold China exercises on the media is already sliding quickly into a stifling environment that will naturally become a barrier to innovation. Innovation cannot go unchecked, but erecting walls around it is how it dies.

Only two weeks ago, China began enforcing a controversial cybersecurity law that many see as a censorship law dressed up in the costume of national security. The law has been noted by analysts to threaten not only its own people’s freedom to speak and think (two integral ingredients for innovation), but also foreign corporations’ intellectual property and global connectivity.

SEE ALSO: China: Upcoming Cybersecurity Law feeds concerns of foreign firms

As a result of the law, corporations must retain their data within China’s borders, and their ability to access foreign web services will be greatly affected by their inability to access virtual private networks (VPN).

It’d be irresponsible to see the government’s actions towards Liu’s death and the increasingly restrictive cybersecurity policies as unconnected – they are both products of the country’s approach to censorship. Foreign corporations would do well to remain wary of China, and remain vigilant of the fact China always comes first. In large part, the foreigners are collateral, and they too could become the focus of a harsh government crackdown.

For the part of the Chinese government, it would do well to remember its policy in the past of allowing a little freedom, a little to leak through, worked to keep its population complacent and quiet. Stricter policing could have a bigger backlash than they anticipate, and the last thing they need is citizens curious enough to go poking around corners of the Internet they don’t want seen.

READ MORE

- The criticality of endpoint management in cybersecurity and operations

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach

- Insurance everywhere all at once: the digital transformation of the APAC insurance industry