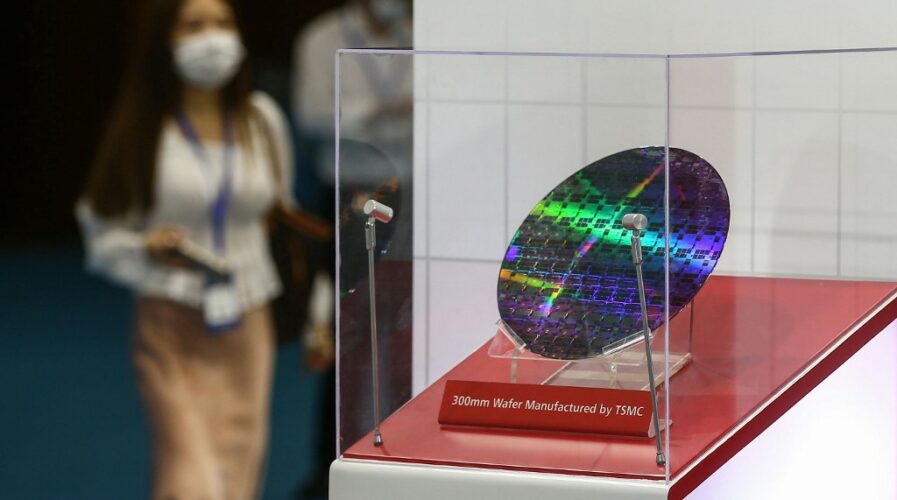

A chip by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) at the 2020 World Semiconductor Conference in Nanjing, China. Source: AFP

Taiwan — the unlikely frontier for the global tech arms race

- A series of unexpected events has both the US and China out to solidify their source of semiconductor chips

- It’s putting the spotlight on Taiwan’s unsung semiconductor industry

The global technology trade war took some unexpected turns as we crossed the midpoint of 2020. Unsurprisingly, the world’s two largest economies — the US and China — are right in the thick of it, firing the latest salvos in a simmering standoff. But the surprise flashpoint is turning out to be the unheralded, yet crucial, Taiwan semiconductor industry.

At the center of it all is the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). TSMC might not be a household name like Apple, but semiconductor foundries like TSMC are essential to the production of devices like the ubiquitous iPhone.

Semiconductor manufacturing is essential tradecraft, a critical component of high-performance electronics. Found in everything from smartphones to guided missiles. Now, TSMC is basically the Hermès of silicon chip-making, producing high quality, super-advanced microchips at a large production scale.

Top electronic brands do not manufacture their own chips but procure them from TSMC, which controls around half of the worldwide chip-making market, ahead of both South Korea’s Samsung and the US-based Intel. This pivotal position at the center of the global semiconductor trade has drawn sharper focus ever since China and the US renewed trade hostilities, as both superpowers attempt to assure their own supply of precious semiconductors while politicking around the other.

The latest offensive sees the American Trump administration clamping down further on restrictions it had imposed on China’s tech juggernaut Huawei. In May, the US Department of Commerce expanded prohibitions that were intended to force all semiconductor chip manufacturers who use US “chipmaking equipment, intellectual property or design software will have to apply for a license before shipping chips to Huawei.”

TSMC relies on American tech to manufacture its quality chips, and any application for an export license to Huawei and its chip subsidiary HiSilicon would likely be denied, as the US tries to keep 5G technology leader Huawei out of the global 5G network loop.

This prevented TSMC from taking further orders from Huawei, which had been providing 13% of its revenue stream, including making the chips for Huawei’s 5G base stations. Losing its biggest Chinese customer was offset in late July when rival Intel was hit by major manufacturing delays to its 7-nanometer chips production and announced it may outsource production.

TSMC’s advanced processing chip business dwarfs nearest rival Samsung’s, and the news of the potential order caused TSMC’s stock to skyrocket by nearly 50% – the knock-on effect to TSMC’s valuation placed it among the top 10 most valuable companies on the planet.

The Taiwan semiconductor trade at a glance

The Taiwan semiconductor trade (including United Microelectronics Corporation which holds around 7.3% of the global market, plus other smaller players) is in a unique position between the crosshairs of the two global superpowers. Long at political loggerheads with China and sometimes an (unofficial) ally of the US, profitable business ties with the two depend on an open trade market.

This is especially true for TSMC, which has gone as far as building a US$12 billion manufacturing plant in Arizona to appease the Trump administration, which wants to have more cutting-edge chip-making capabilities within the US.

Despite frosty diplomatic relations, TSMC is China’s biggest contract supplier, making chips for the likes of smartphone giant Xiaomi, computer maker Lenovo, and electric-vehicle (EV) firms. Between COVID-19 fallout and American sanctions, China’s booming tech economy might be caught out if it cannot access the world’s biggest and most reliable semiconductor chip maker to boot.

READ MORE

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach

- Insurance everywhere all at once: the digital transformation of the APAC insurance industry

- Google parent Alphabet eyes HubSpot: A potential acquisition shaping the future of CRM