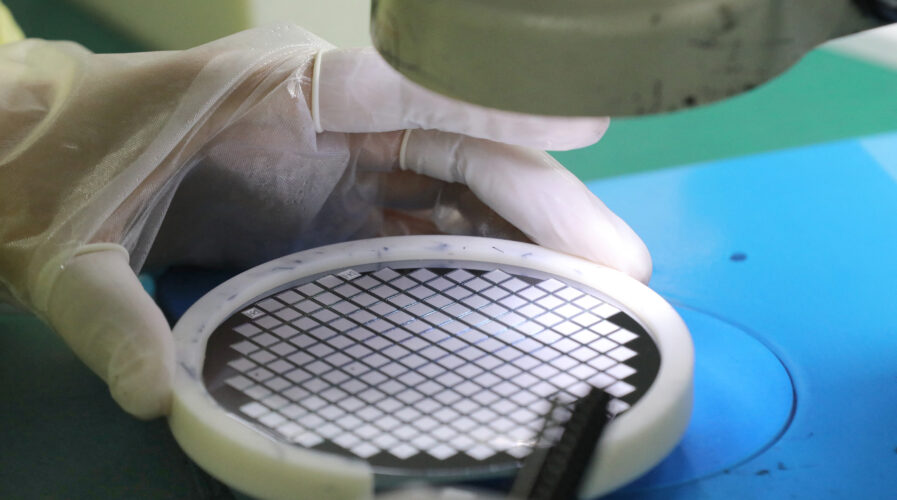

Semiconductor chips conundrum; From a chip draught to chip glut. (Photo by STR / AFP) / China OUT

The semiconductor chips conundrum – from chip draught to chip glut

- The global chip shortage is far from over, and analysts have several outlooks regarding its evolution.

- While some estimate that the chip shortage will outlast the Covid health crisis, other analysts warn that it could lead to market saturation in the near future.

Since last year, automakers and electronics producers have been facing a shortage in semiconductor chips—the components vital to controlling onboard computing functions. The apparent chip drought had stirred panic among manufacturers, leading to increasing orders to secure future supplies. Chipmakers on the other hand were responding by expanding their capacities.

Now, as players innovate, shortage may no longer be an issue. Rather, the imbalance between demand and supply risks swinging the other way, as analysts warn a chip drought could become a chip glut. In other words, chip manufacturers might have invested too heavily in increasing their capacity, which could lead to an overcapacity over time.

This is especially so since some automakers are considering switching production strategies, which would reduce reliance on massive orders of chips and other outsourced components. The latter would bring a shift in wait times for deliveries, as well as a potential need to rethink various elements on the supply chain.

According to a report by Bloomberg, the current wait to actually get a chip after you order it across the industry is 14.1 weeks, up from about 13 weeks in January. Anything above 14 is the “danger zone.” To top it off, the industry is notoriously cyclical and the current upswing has been dramatic, according to the report, adding that revenue across the sector rose 1.6% in (typically slow) January versus the prior month.

“That’s the first time this has happened in more than two decades and it’s 11 percentage points above the typical seasonal sales pattern, according to UBS. Double ordering is probably contributing to this,” it added.

South Korea’s Samsung with Taiwan’s TSMC control over 70% of the semiconductor manufacturing market, with the latter being the biggest player in the industry at the moment. To recall, back in May, South Korea announced plans to invest US$450 billion to boost its chip production. The investment is channeled through several channels, including tax breaks, for companies that operate in the country.

The current administration of the US is also considering ways to bring manufacturing back on American soil to reduce the reliance on various chipmakers and ensure a better supply for domestic industry. The Biden administration plans to allocate US$52 billion in incentives for the domestic semiconductor industry via a bill Congress is currently debating. At the same time, China is also investing heavily in new factories that will allow it to up its chip production, and all the above could lead to market saturation.

The EU too has committed US$160 billion of Covid recovery funds to develop regional tech capabilities as it aims to boost the bloc’s share of semiconductor manufacturing to 20% of the global total by 2030. In June, analysts at consultancy Bain & Company said building capacity would “hurt the economics” of suppliers since each will likely run production lines below capacity once demand abates.

Industry analyst Daniel Nenni told Fortune there would be a glut unless “there is some big boom in semiconductor demand” beyond the current panic buying. Once the panic subsides, the world could find itself with too many chips. But analysts warn that China—the country most desperate to secure a domestic chip supply—could suffer a glut more easily than its peers.

READ MORE

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach

- Insurance everywhere all at once: the digital transformation of the APAC insurance industry

- Google parent Alphabet eyes HubSpot: A potential acquisition shaping the future of CRM