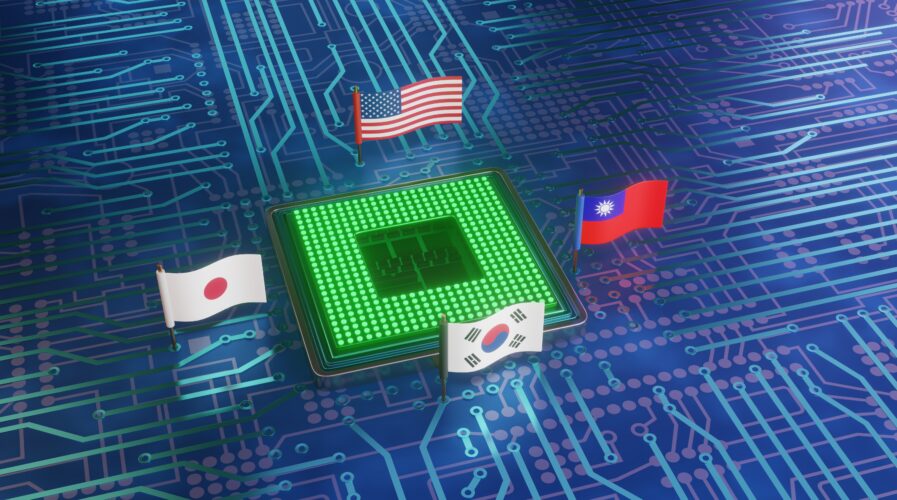

The Chip 4 Alliance has remained as a proposed working group with no clear indication on when it will be fortified.(Source – Shutterstock)

Is there really a Chip 4 Alliance? Officially, it’s still a proposal

In March 2022, US President Joe Biden proposed a technology partnership to build a semiconductor supply network known as the Chip 4 Alliance. The alliance suggested by the US includes Asian semiconductor powers such as South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, with the goal to keep China’s fledgling chip industry at bay.

When the idea first came about, many questioned the rationale behind the US pushing a possible grouping between itself and the East Asian tigers, and what it does for the semiconductor value chain. For the US, it wanted a forum for governments and companies to discuss and coordinate policies on supply chain security, workforce development, R&D and subsidies.

To the rest of the world, it was clearly a strategy by Washington to strengthen its access to vital chips and weaken Chinese involvement, on trade and national security grounds. After all, for the US to fortify its supply chains on top of all restrictions imposed against China, it needs alliances. However, it has been more than a year since the proposals were first drawn up, yet the four countries have not finalized the alliance, let alone signed any agreements or treaties.

Therefore, to date, the Chip 4 Alliance has remained as a proposed working group with no clear indication on when it will be fortified.

How were the members of the Chip 4 Alliance picked?

It is important to understand that the initiative includes Japan, South Korea and Taiwan because each state excels in certain areas of the semiconductor industry. When the ways that each place contributes to the supply chain is scrutinised, it’s obvious why the US chose those nations.

Firstly, being a design powerhouse and holding all Electronic Design Automation (EDA) tools licenses, the US controls the fabless market via its private firms. Undoubtedly, the US also has the most semiconductor fabrication facilities in the world. Then there’s Taiwan, the global epicenter of semiconductor manufacturing, with over 60% of the world’s chips being manufactured by the country’s giants, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and United Microelectronics Corp (UMC).

Taiwan is also a hub for all Assembly, Testing, Marking, and Packaging (ATMP) processes through domestic firms like Foxconn and Winstron. As for South Korea, the country also houses semiconductor behemoth, Samsung, with both design and manufacturing capability. Then there’s Japan that remains integral to the functioning of the supply chain with its dominance over the production of critical manufacturing equipment and materials such as photoresists.

All in all, the Chip 4 alliance covers all the major areas of the value chain. Although there are other dependencies and bottlenecks, it is safe to say the four states, should the alliances materialize, can run semiconductor production more efficiently together. However, the elephant in the room, that might prevent the alliance from taking shape, is China and the force of its market.

US President Joe Biden proposed the Chips 4 Alliance in March 2022. (Photo by SAUL LOEB / AFP)

State and their US-China conundrum

In South Korea, the government and private sector appear to be wary of the implications and the potential restrictions that might be imposed on them by China mainly due to the fact that China remains the biggest market for local semiconductor companies. Looking into the data from the Korea International Trade Association, Mainland China and Hong Kong account for around 60% of Seoul’s semiconductor exports.

Since South Korea is a global leader in memory chip production, China remains its biggest trading partner, accounting for over 48% of South Korea’s memory chip exports. Even Taiwan has been finding themselves in a crossfire: having the US as their security ally and China as their top trading partner. Taiwan specifically has been the beneficiary of worsening relations between Washington and Beijing — however, it has been anything but a smooth sailing journey for the country that is home to the world’s most significant chip player.

Democratic Taiwan, which China claims as its own, has come under increasing military and political pressure from Beijing, especially after Chinese war games in early August following a Taipei visit by US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Data also shows that Taiwan depends more on China for trade than it does on the US.

In 2021 alone, mainland China and Hong Kong accounted for 42% of Taiwan’s exports, while the US had a 15% share, according to official Taiwan data accessed through Wind Information. In all, Taiwan exported US$188.91 billion in goods to mainland China and Hong Kong in 2021. More than half were electronic parts, followed by optical equipment, according to Taiwan’s Ministry of Finance.

Recently, Taiwan has bought an increasing number of products from mainland China, and vice versa. Over the last five years, Taiwan’s imports from mainland China have surged by about 87% versus 44% growth in imports from the US. Taiwan’s exports to mainland China grew by 71% between 2016 and 2021. At this point, it is clear that Taiwan’s economy will not be able to decouple from its biggest trade partner, China.

Exports to the US did nearly double between 2016 and 2021, growing by 97%. Top US purchases of Taiwan’s goods include electrical machinery, vehicles, plastics and iron and steel products, according to US government data. Japan is the only other country besides Taiwan to restate its commitment wih the US to restrict hi-tech exports to China since the preliminary meeting.

During a visit at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies think tank in Washington, Japan’s minister of economy, trade and industry, Yasutoshi Nishimura said “it is also absolutely imperative for us to reinforce our cooperation in the area of export control”. Nishimura reckons the move is important especially “to address the misuse of critical and emerging technologies by malicious actors and inappropriate transfers of technologies.”

All in all, for the US, the alliance is also a framework to drive technological breakthroughs and to withstand supply disruption emanating from trade conflicts or geopolitical tensions. Nishimura also said Tokyo wanted to work more closely with Washington to jointly develop dual-use technologies, citing rising military challenges from Beijing following tensions across the Taiwan Strait.

For now, the idea of Chip 4 Alliance remains overblown with little to no update on its progress or future.

READ MORE

- The criticality of endpoint management in cybersecurity and operations

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach

- Insurance everywhere all at once: the digital transformation of the APAC insurance industry