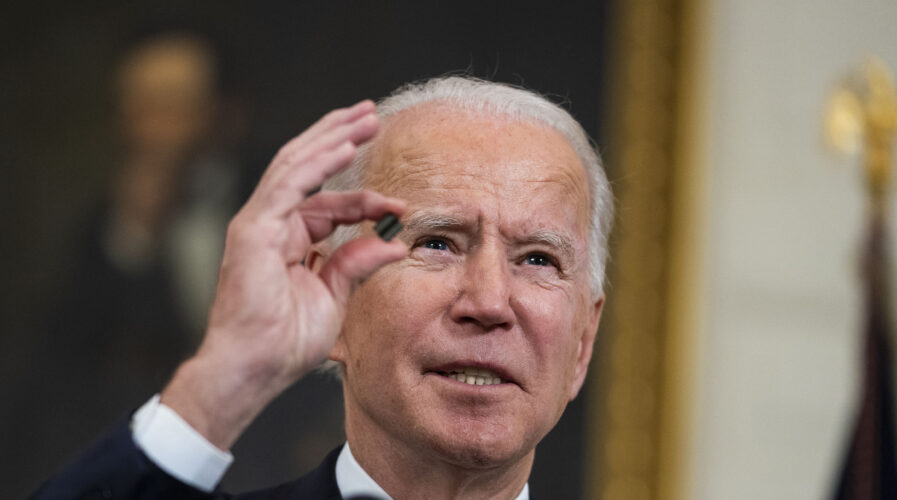

Is the world too dependent on Asia’s semiconductor industry? (Photo by POOL / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / Getty Images via AFP)

Is the world too dependent on Asia’s semiconductor industry?

- The Asia Pacific is also the world’s biggest market for semiconductors, accounting for 60% of global semiconductor sales, with China alone accounting for over 30%

- Intel believes it is not “palatable” that so many computer chips are made in Asia

- Now, Intel plans to spend US$20 billion on US chip plants to challenge Asia dominance

The shortage in chips, considered as the “brain” within most performance electronic devices in the world, has been steadily worsening since last year. What started as a temporary delay in supplies within the semiconductor industry, turned into an ongoing crisis as production quotas return to normal, thus causing a new surge in demand.

In fact, the production of semiconductors has steadily declined in the west, with East Asia emerging as the main manufacturing hub. Within the Asia Pacific region alone, China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan together have become the “Big 4” semiconductor players, holding four of the top six spots by overall semiconductor revenue and each has several global semiconductor giants. The region is also the world’s biggest market for semiconductors, accounting for 60% of global semiconductor sales, within which China alone accounts for over 30%.

The US’s share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity fell from 37% in 1990 to just 12% last year, while Europe saw a 35 percentage points decline in the period, to 9%. China’s mainland expanded its share from almost nothing to 15%, a figure that is expected to rise to 24% in the next decade, according to analysts.

The severity of the shortage

The global semiconductor chip shortage today is so severe that it has reached the extent of United States (US) President Joe Biden signing an Executive Order to address the issue. Designed as a 100-day review of supply chain effectiveness, and citing that the US accounts for 12.5% of semiconductor manufacturing, the EO is a part of a continuous stream of policy assuming that made in America is good for America.

Take Apple for an instance, a US$2 trillion company and the world’s biggest buyer of semiconductors spending US$58 billion annually, was forced to delay the launch of the much-hyped iPhone 12 by two months last year due to the shortage. Ford recently canceled shifts at two car plants and said profits could be hit by up to US$2.5 billion this year due to chip shortages, while Nissan is idling output at plants in Mexico and the US General Motors said it could face a US$2 billion profit hit.

Sony, which along with other gaming console makers has struggled with stock shortages over the last year, said it might not hit sales targets for the new PlayStation 5 this year because of the semiconductor supply issue. Microsoft’s Xbox has said it forecasts supply issues continuing at least until the second half of the year. Yet, the most telling example of the semiconductor crisis has come from Samsung, the world’s second-largest buyer of chips for its products after Apple.

Earlier this week, the company said it might have to postpone the launch of its high-end smartphone due to the shortage, despite also being the world’s second-largest producer of chips. It is astonishing considering that Samsung sells US$56 billion of semiconductors to others, and consumes US$36 billion of them itself, finds it may have to delay the launch of one of its own products.”

The most recent move was by Intel’s new chief executive, Pat Gelsingerwho, who told the BBC that it is not “palatable” that so many computer chips are made in Asia. As a result, Intel will greatly expand its advanced chip manufacturing capacity as Gelsinger announced plans to spend as much as US$20 billion to build two factories in Arizona and open its factories to outside customers.

In short, the strategy will directly challenge the two other companies in the world that can make the most advanced chips, Taiwan’s Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Korea’s Samsung Electronics. It will aim to tilt a technological balance of power back to the US and Europe as government leaders on both continents have become concerned about the risks of a concentration of chipmaking in Taiwan given tensions with China.

A report by Deloitte stated that businesses should also consider that over-reliance on one region could jeopardize their ability to continue business-as-usual. Add to this the risk of ever-more-frequent unforeseen disasters, and it becomes apparent that companies need to reconfigure their global value chains to mitigate and manage risks in advance.

“Businesses should first assess their supply chain risks, and look to diversify their supply chains by building up parallel networks—more fragmented but tightly managed value chains to diversify risks. This requires longer-term, scenario-based analysis of risks and opportunities, rather than simply shifting to a lower-wage country,” the report stated.

READ MORE

- The criticality of endpoint management in cybersecurity and operations

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach

- Insurance everywhere all at once: the digital transformation of the APAC insurance industry