Malaysians often readily give up personal information, although the state of data protection literacy and practice in the country can be rather abysmal (Yeexin Richelle / Shutterstock)

Malaysia’s chronic indisposition to prioritize data protection will ruin us all

Data protection, as well as data security and privacy, aren’t talked about enough in Malaysia. Sure, data leaks, in general, are nothing new, especially in the age of increasing digital use and data production.

However, it’s a whole new different ballgame when it comes to data leaks from official databases, such as government institutions or commercial entities such as credit agencies.

The 2021 Malaysian government data leak

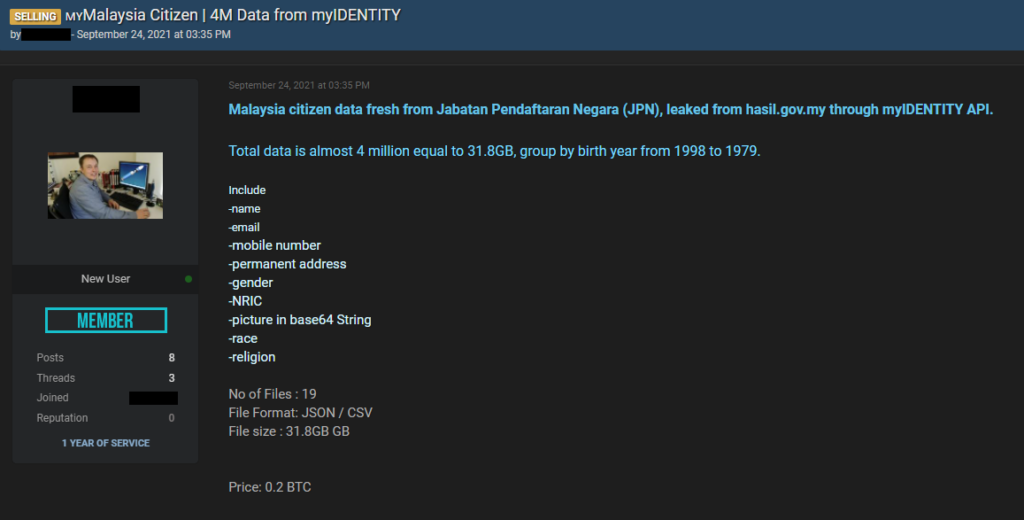

In late September last year, a Twitter post by Malaysian Cyber Intelligence Specialist Adnan Shukor broke disturbing news that the personal identities and information of approximately four million Malaysian citizens were on sale on a popular leak site.

In that incident, it was claimed by the seller on the site that these are “fresh” data obtained by the Malaysian National Registration Department (NRD), or, Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara (JPN).

Tech Wire Asia spotted the original source originating from the online seller, who wanted 0.2 BTC (US$8,480, or, RM 35,459) for the entire list comprising information on four million Malaysians.

Screenshot of sale post of Malaysian citizen data on an internet forum [Source: Tech Wire Asia]

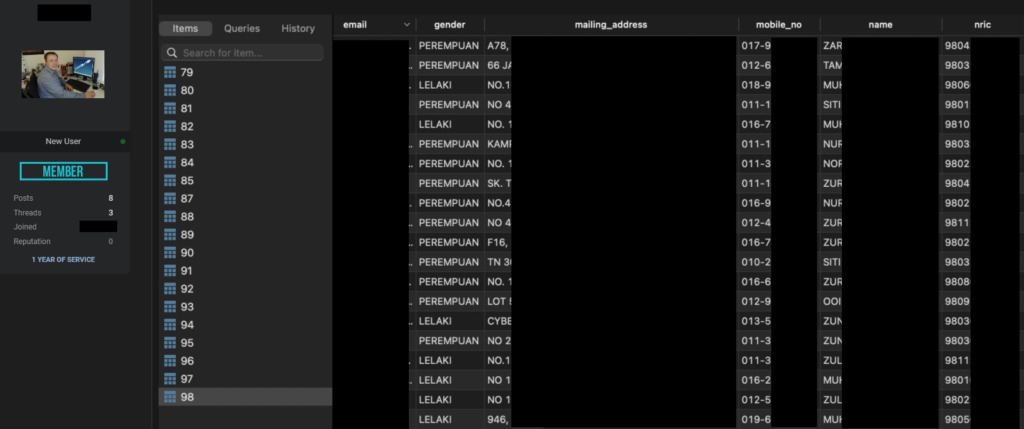

The information peddled was extremely comprehensive, including details such as the citizen’s full name, date of birth, email, gender, contact number, and residential and mailing addresses.

This information was contained in a JSON file and also uploaded as evidence of the goods:

More concerningly, a related leak of data from 4 million taxpayers from the country’s Inland Revenue Board (LHDN), was also being sold by a different user, in a similar file format.

Unlike the NRD database, this contained information such as the individual’s name and personal details, as well as household incomes, and similar information on their spouses.

Attitudes towards data protection

Globally, users who utilize online platforms or sites and share and post personal information of themselves are getting increasingly aware of the importance of keeping such data secure.

Half a decade back, most people wouldn’t give much of a thought to data security, although the Cambridge Analytica scandal did rock the world and bring the issue to the fore.

However, it seems Facebook — sorry, Meta — has not learned its lesson.

Over in Southeast Asia, tech giants have been taken to task for data privacy breaches, with a prominent one being Grab.

However, over in Malaysia, there’s only a handful of players championing the cause for stronger data protection and its associated policies.

One is Sinar Project, a civic tech initiative using open technology, open data, and policy analysis to promote accessibility of information to the Malaysian people. In recent times, they’ve also explored digital rights, but with a lesser focus less on the tech, and more on policymaking.

Conversely, the IO Foundation (TIOF) sees the problem of digital rights as a tech issue more than a policy or political issue. TIOF is an international non-profit based in Malaysia that envisions a world where the digital rights of users are protected — by design.

TIOF’s Spanish-French founder, Jean F Queralt, is no stranger to Southeast Asia and has been contending with this issue for the last twenty years. TIOF also advocates that the digital rights of users be on par with human rights, especially since we are fast hurtling into an age of excessive data and digital identities.

Both The IO Foundation and Sinar Project regularly conduct training workshops and seminars to educate the public as well as private sector players and civil servants.

Evangelizing data protection and the PDPA

Tech Wire Asia reached out to some cybersecurity experts and had the opportunity to speak to Fong Choong Fook (or CF Fong), Director of LE Global Services, an IT security MSP, on the data breaches, as well as data security and data privacy.

Data security and privacy laws in Southeast Asia generally still leave much to be desired. Both Singapore and Malaysia have laws concerning these, called the Personal Data Protection Act, commonly referred to as PDPA.

Both these acts regulate the processing of personal data by companies or within commercial transactions in Singapore and Malaysia, so as to safeguard the personal data of users and customers from misuse.

Alas, it’s not that we don’t have laws and regulations here for data protection and data privacy. The issue is that, despite the existence of these laws, data breaches and leaks still happen.

It is especially worrying in Malaysia, where highly sensitive information of over four million citizens can be brazenly sold online for as little as RM 35,495 (US$8400).

It’s a double whammy, in that this alone shows just how insultingly little our data is valued, and how easy it is to access these data, which can expose the victim to a litany of digital, financial, and even physical risks.

Importance of data protection and the PDPA

Fong shared that the public sector, i.e. both the Federal and State governments themselves, as well as their related bodies, are not bound by the PDPA.

It is interesting to note the irony of the Malaysian government imposing the PDPA on companies (or those engaging in commercial transactions) to safeguard personal data — yet are themselves allegedly incapable of protecting highly confidential citizen data.

Whether these data leaks are through digital or physical means is irrelevant.

The fact of the matter is that these leaks have happened, and the damage has been done — the personal, highly sensitive, and powerful data of citizens are now on the world wide web.

Fong is no stranger to cybersecurity and data leaks, having been in the industry for decades. He is a PDPA evangelist, if you may, and emphasized multiple times in our chat, the importance of the act.

He opines that both the private and public sectors need to know what the PDPA is, be aware of its importance, and enact them in practice.

“The private sector needs to have policies established, and be very aware that the management personnel are actually liable for prosecution, should the company fail to adhere by the PDPA.”

“The penalties that come with a breach of the PDPA aren’t to be taken lightly, and organizations should be alert to these”.

Malaysia’s problematic attitude towards data protection

Fong segued a little into the cultural aspects of the Asian Malaysian society — and agreed that we are steeped in a culture that fails to respect privacy.

This is possibly one reason why adherence to data protection and data privacy values or even policies are incredibly lax in the nation.

It’s not just the large companies that need to abide by data protection and privacy policies — a huge amount of SMEs here also collect sensitive personal data.

And when one actually examines their practices, one would find that there is little to no regard for proper practices to safeguard data.

One clear example of this lack of care can be seen in how Malaysian companies collect and process employee information.

Many SMEs who haven’t quite digitalized still fully rely on physical folders and files to hold data on employees — or even jobseekers!

All it takes is for an unauthorized person to enter these offices and rifle through the folders to get sensitive data on individuals.

It can be quite mindboggling to contend with the fact that, in 2022, there are still employers here who require prospective employees to divulge highly sensitive information.

These include data such as their date of birth, identity card number, tax file number, address, details of family members, or even health history.

It is also common for commercial entities such as pharmacies or F&B establishments to collect personal data such as names and identity card numbers presumably to register as a member, even though there is absolutely no reason why such sensitive personal data should be given up.

Worse still — these companies would never declare nor reassure job seekers or customers about how their data is processed and stored. It might be even harder to request that they be destroyed.

The previously jovial air during our interview changed, as Fong’s voice took on a more somber tone.

“The data that we’re collecting is accumulating, and it will get increasingly harder for us to protect them, and our people, if we do not have best practices or guidelines in place.

Fixing the problem

Throw a stone at a random company in Malaysia that handles personal data, and you’d quickly find that a lot of them have no idea what the PDPA is. Even if they have heard of it, frequently, they’d have no idea how to implement them.

Ensuring adequate and effective processes and guidelines, as well as enforcement, seem to be a recurring plague within the various strata of Malaysian society — and, as many a Malaysian would enthusiastically agree, — governance.

When asked how companies can go about establishing these guidelines and practices to ensure better data protection, Fong opined that the process isn’t as complicated as most think.

“Firstly, to implement a policy, you’d need procedures. These procedures would then need to be supplemented by clear guidelines and skills training.

“A good place to start would be to visit the website and download a copy of the Personal Data Protection Act 2010. Read through it to understand, in principle, what it is about, and what you ought to look out for.”

“Of course, it would be much easier for companies to engage a lawyer to draft a PDPA policy too. Saves you the hassle, too”, he added, with a laugh.

Is more legislation better?

In 2017, the entire country was affected by a massive data breach where details of owners of mobile numbers by telcos were leaked. Hackers attempted to sell off the data of 46 million mobile phone owners in Malaysia, making it Asia’s largest data breach to date.

Mind you, the PDPA was enacted in 2010 and amended in 2013. Even so, these holders of our data could not secure our data properly.

In reaction to the 2021 government-related data leaks, certain quarters have called for stricter legislation.

There is an argument to be made that instituting new laws to handle data leaks or breaches, whether sold on the dark web or otherwise, may not be particularly helpful.

A reactive approach to (cyber)crime isn’t ideal for two reasons; firstly, the principle of deterrence through punishment is only effective when enforcement is consistently and equally enforced (e.g. without the baggage of corruption).

Secondly, like other crimes, the damage, often irreversible, would already be done to victims. The only recourse or compensation available is often monetary, and the legal process to obtain the monies back may be long and arduous.

Instead, focusing on developing a holistic and preventative approach would be ideal, and this doesn’t just mean introducing more legislation.

Malaysia already has the PDPA, which, for the most part, may be described as decent. Unfortunately, it suffers from a lack of enforcement (as do many other important things in the country).

Secondly, there is a dearth of data protection and data privacy literacy in Malaysia. A lack of coordinated educational campaigns have made us all ignore the importance of securing our data, or holding companies and governments accountable for the misuse or manhandling of our data.

There is a lack of transparency and accountability; data privacy literacy; adherence to and enforcement of protocols, and enactment of established procedures for collection and use of personal data in Malaysia.

These are the core kinks in the system that need to be ironed out — it is not a problem that can be easily solved by slapping a legislative band-aid and hoping it resolves itself.

This would be especially more urgent as Southeast Asia heads into the golden age of e-Commerce and soon, the metaverse.

Ensuring data protection and privacy requires an overhaul of attitudes — there needs to be a drastic shift of mindsets and especially urgency to recognize these as priorities.

The views expressed here belong to the author and does not represent Tech Wire Asia.

READ MORE

- Safer Automation: How Sophic and Firmus Succeeded in Malaysia with MDEC’s Support

- Privilege granted, not gained: Intelligent authorization for enhanced infrastructure productivity

- Low-Code produces the Proof-of-Possibilities

- New Wearables Enable Staff to Work Faster and Safer

- Experts weigh in on Oracle’s departure from adland