Personal hygiene online starts with the person: LastPass by LogMeIn

There are several interesting statistics among the horror story that is the OAIC NDB Report for April – June 2019 (the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, Notable Data Breaches).

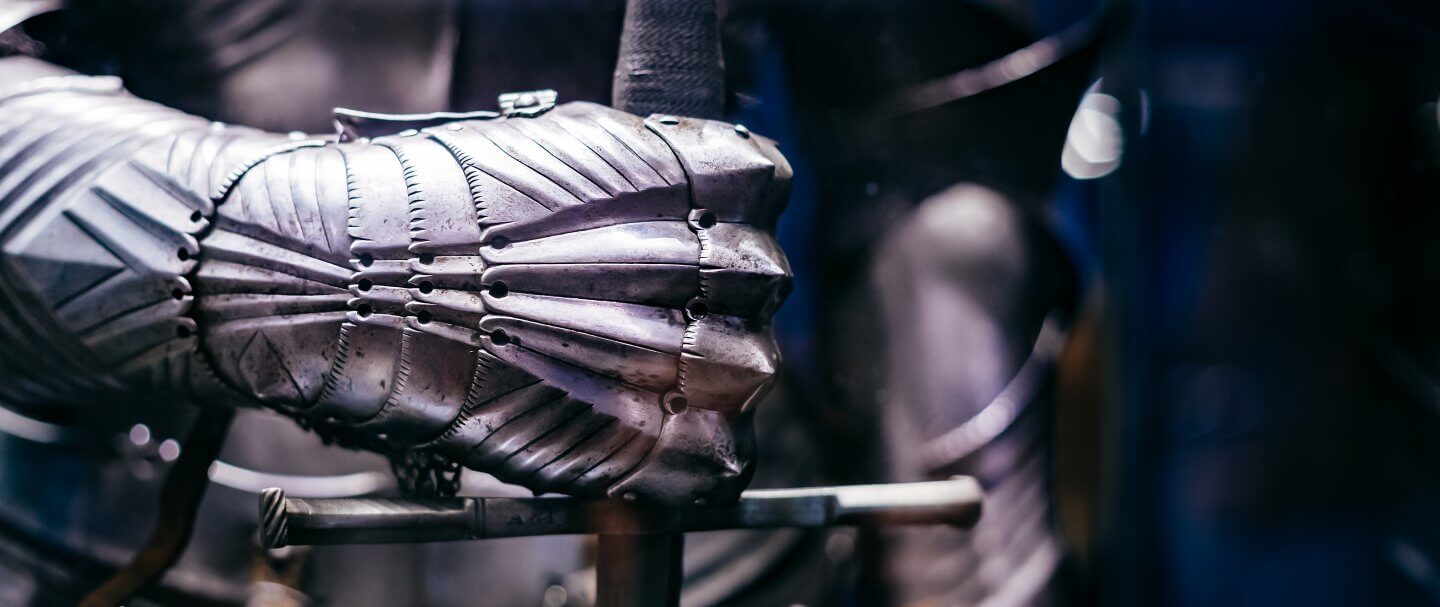

The first is that, of the data breaches in those three months, only 12 percent were the result of brute force attacks or hacking. Those are the type of attacks that Hollywood is fond of, usually depicted by lone figures in darkened rooms, tapping at a keyboard.

The reality is somewhat different in most cybersecurity incidents. Those attacking networks usually operate in groups, and those groups are dominated by organized crime syndicates who are looking for financial gain.

Their methods are dominated by exploiting individuals with phishing campaigns (resulting in 44 percent of notable incidents), or by using compromised credentials from unknown sources (30 percent). In many cases, the “unknown sources” are the lists of identities, credentials, and other information available for sale on the “dark web”.

But what’s important to consider among those statistics is “not that it’s [information] stolen, but how it’s used.” Those are the words of Brian Hay, an ex-Police Detective Superintendent, with 37 years’ experience in the Queensland Police Force, and the person in operational command of the force’s Cybercrime Group.

Until any person or company is a victim of cybercrime (such as identity theft), it’s impossible to imagine how terrible the effects can be. As well as the personal financial loss for the individual, the impact on the victims can last years. For organisations that have been breached, it can easily be the end of the business altogether — if not immediately, then after many months of attempting to unravel the long-term effects.

Furthermore, a report from Verizon shows that after a successful cyber attack, 60 percent of small businesses cease trading as a result.

Financing perimeter defenses?

Human nature is such that most people consider cybersecurity defense to be a technology issue: the hardware installed in the data centre’s racks that examines network traffic and blocks incursions. While those physical boxes with their flashing lights are indeed valuable, why do over 90 percent of attacks begin with a phishing email, directed at a person, not a device? The answer is that most people’s online behaviour effectively paints an easy target on their backs. In short, it’s a personal, not a technological issue. Or, as Hay says, “It’s personal, it’s real, it’s widespread; it’s organized crime.”

Organisations need to shift their security focus to the source of the majority of successful attacks: the people that work in the company. The problem isn’t with employees giving away or losing sensitive information (although that does occur in a small minority of cases). Instead, it’s each individual’s personal cyber hygiene habits that need to change — and companies can ensure that improves by spending just a few dollars on each individual.

Same old, same old

The recommendations by cybersecurity specialists are clear on this score: use unique passwords for every account you use, don’t share any credentials, like username or password, and don’t use simple passwords. Ever.

What’s not so often said is that that practice must be carried out absolutely everywhere. As soon as someone uses the same password twice, that opens the door to identity theft and the potential — eventually — of the company having to fold. And while that might sound melodramatic, it happens every day, not just across the APAC region, but across the world. Here’s a simple example:

Your new office manager sets up his or her new account to gain access to a file-sharing store. They use the same password they used a year ago to let one of their kids get access to an online game. It’s a good password (that is, not “qwerty” or “p4ssword”), but to save having to remember yet another password, they used the same one. And truth be told, they use that same password nearly everywhere: Netflix account, local library website, laptop login, and so on.

Unknown to your new office manager, the kids’ gaming site got hacked a few months ago, and their email address and password are now for sale on the dark web. And now, organized crime has the keys to dozens of online accounts, including access to the company’s sensitive data.

Highly cost-effective fixes

The simple answer is to get and use a password manager app. Many cyber protection companies like LastPass even give away a free version to individuals. LastPass works across all devices (laptops, desktops, tablets and mobiles), letting users create new passwords whether on the go or in the office. It also works with browsers, giving the freedom to use a preferred browser or device safely at all times.

If every person in every organization took that simple step, then cybercrime figures would be slashed overnight. Crime gangs buying hacked credentials would have vital information missing, especially the passwords that would unlock other areas of the victim’s life.

For business leaders, the relatively small investment in a business plan for a password manager (and ideally, an enterprise password management system to automate and extend control over all aspects of system access easily) would protect both all systems in-house and in the cloud. Plus, it would also better protect the weakest point in their organizations’ defenses, the people that add value to a business, every day.

Better than the local library’s systems?

What a password manager like LastPass by LogMeIn for Business offers is a further facility that’s thankfully becoming more common. Multi-factor authentication (MFA) adds a belt-and-braces approach to business and personal security, by making any person attempting to gain access to company systems identify themselves by another means than just a username and password; typically, that’s a biometric identification (fingerprint, facial scan) coupled with a device that the user has access to. This provides best authentication practices — validating by something you have (a mobile device), something you are (a biometric) and something you know (a password). Having MFA coupled with a password manager creates a really strong barrier to cyber criminal entry that can span the entire organisation and cover nearly every use-case for accessing systems and applications securely.

A decent password manager prevents staff from sharing passwords and logins, and also lets supervisors track every access attempt, and, for instance, turn off access for employees leaving the company. But you can learn more about those and other advantages of a password management systems in a professional setting by reading more here.

READ MORE

- Strategies for Democratizing GenAI

- The criticality of endpoint management in cybersecurity and operations

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach