(Source – Shutterstock)

New APT group Dark Pink targeting governments in APAC

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Advanced persistent threat (APT) groups continue to wreak havoc around the world, often targeting government agencies and organizations. As most APT groups are state-sponsored, most of their tactics often go undetected for a long time. APT groups are also known for leaving backdoors when infiltrating systems after stealing data or spying on their targets.

Some of the most popular APT groups include APT41, a prolific cyber threat group that carries out Chinese state-sponsored espionage activities in at least 14 countries since 2012. Another example is APT 39, which targets the telecommunications sector. Suspected to be from Iran, the group primarily leverages the SEAWEED and CACHEMONEY backdoors along with a specific variant of the POWBAT backdoor.

While there are several other high-profile APT groups, cybersecurity vendor Group-IB has published findings into Dark Pink, an ongoing APT campaign launched against high-profile targets in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

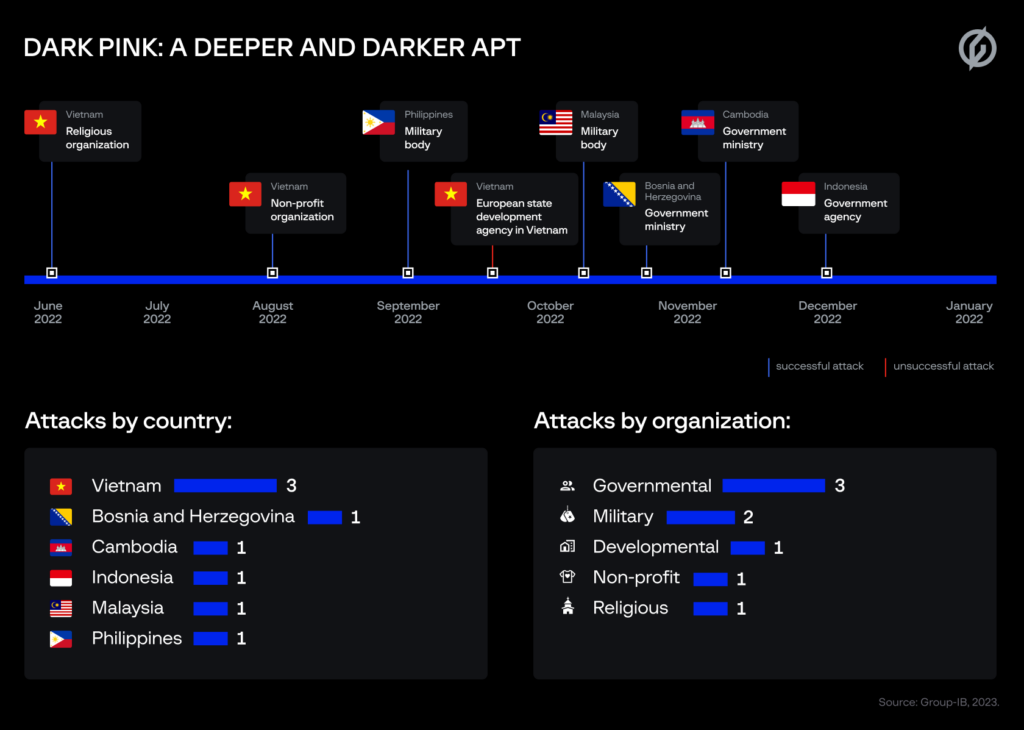

Group-IB believes the campaign was launched by a new threat actor, which has also been termed Saaiwc Group by Chinese cybersecurity researchers. This new APT group is notable due to its specific focus on attacking branches of the military, and government ministries and agencies. To date, Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence has been able to attribute seven successful attacks to this particular group from June-December 2022, with targets including military bodies, government ministries and agencies, and religious and non-profit organizations, although the list of victims could be significantly longer.

The first successful attack took place in June 2022, when threat actors gained access to the network of a religious organization in Vietnam. Following this particular breach, no other attack attributable to Dark Pink was registered until August 2022, when Group-IB analysts discovered that the threat actors had gained access to the network of a Vietnamese non-profit organization.

Dark Pink’s activity ramped up in the final four months of the year. Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence Team uncovered attacks on a branch of the Philippines military in September, a Malaysian military branch in October, two breaches in November, with the victims being government organizations in Bosnia & Herzegovina and Cambodia, and finally, in early December, an Indonesian governmental agency. Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence also discovered an unsuccessful attack on a European state development agency based in Vietnam in October.

Dark Pink APT’s timeline and affected organizations. (Source – Group-IB)

While the first Dark Pink breach, as confirmed by Group-IB, took place in June 2022, there are clues to suggest that the group was active as far back as mid-2021. Group-IB found that the threat actors, upon infection of a device, were able to issue commands to the infected computer to download malicious files from Github, with these resources uploaded by the threat actors themselves. Interestingly, the threat actors have used the same GitHub account for uploading malicious files for the entire duration of the APT campaign to date, which could suggest that they have been able to operate without detection for a significant period of time.

How do APT groups like Dark Pink launch successful attacks?

According to Group-IB, Dark Pink utilizes a set of custom tools and sophisticated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) that have made a major contribution to their successful attacks over the past seven months. This included targeted spear phishing emails.

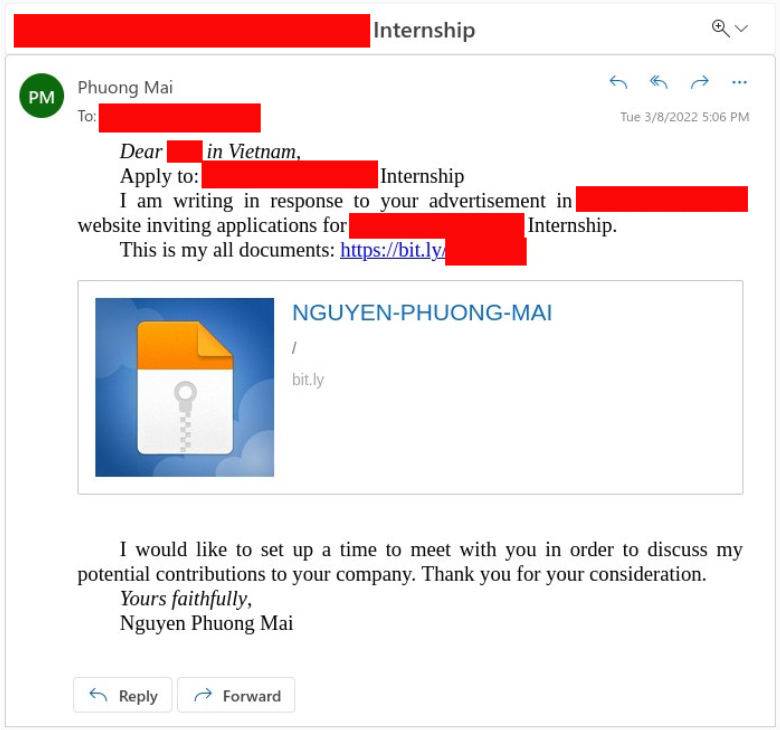

Group-IB was able to find the original email sent by the threat actors in one unsuccessful attack. In this instance, the attackers posed as a job seeker applying for the position of PR and Communications intern. In the email, the threat actor mentions that they found the vacancy on a jobseeker site, which could suggest that the threat actors scan job boards and craft a unique phishing email relevant to the organization that they find.

The spear-phishing emails contain a shortened URL linking to a free-to-use file-sharing site, on which the victim is presented with the option to download a malicious ISO file that always contains three specific file types: a signed executable file, a nonmalicious decoy document (some ISO files seen by Group-IB had more than one), and a malicious DLL file. However, these file types can differ in their content and functionality, and Group-IB analysts uncovered three separate kill chains, underscoring the sophistication of this particular APT group.

Screenshot of original spear-phishing email sent by Dark Pink APT, containing a link to an ISO image hosted on a file-sharing site. (Source – Group-IB)

The sophistication of Dark Pink’s attacks is also underlined by the custom malware and stealers in the threat actors’ arsenal. They created two custom modules, named by Group-IB as TelePowerBot and KamiKakaBot, which are written in PowerShell and .NET, respectively. These two pieces of malware are designed to read and execute commands from a threat actor-controlled Telegram channel via Telegram bot. Group-IB researchers noted that all communication between the devices of the threat actors and victims was based entirely on Telegram API, and they utilized numerous evasion techniques, including Bypass User Account Control, to remain undetected.

The threat actor also created two custom stealers, dubbed Cucky and Ctealer by Group-IB. When launched on the victims’ devices, the thieves can steal passwords, history, logins, and cookies from dozens of web browsers. In this campaign, the threat actors also wrote script that allowed them to transfer their malware to USB devices connected to the compromised machine, and spread their malware across network shares.

The threat actors also leveraged a custom utility, dubbed ZMsg by Group-IB, to exfiltrate data from the Zalo messenger on victims’ devices. Researchers found evidence that the APT group could steal data from the Viber and Telegram messengers as well. One of the only off-the-shelf tools that the threat actors utilized were the publicly available PowerSploit module Get-MicrophoneAudio, which is loaded onto the victim’s device via download from Github. This module, which the threat actors customized to ensure they were able to bypass antivirus software, allowed them to record audio input and later exfiltrate these recordings via their Telegram bot. Group-IB analysts noted that the custom script added to this PowerSploit module was changed multiple times, after several unsuccessful attempts to record the microphone audio on infected devices.

In short, Dark Pink exfiltrated data from victims via three specific pathways: via Telegram, Dropbox, and email.

“Group-IB’s analysis of Dark Pink is of major significance, as it details a highly complex APT campaign launched by seasoned threat actors. The use of an almost entirely custom toolkit, advanced evasion techniques, the threat actors’ ability to rework their malware to ensure maximum effectiveness, and the profile of the targeted organizations demonstrate the threat that this particular group poses. Group-IB will continue to monitor and analyze both past and future Dark Pink attacks with the aim of uncovering those behind this campaign,” commented Andrey Polovinkin, Malware Analyst at Group-IB.

Dark Pink APT’s recent campaign is yet another example of how individuals’ interactions with spear-phishing emails can result in the penetration of the security defenses of even the most protected organizations.

As such, Group-IB recommends solutions, such as its proprietary Business Email Protection, that can counter this threat effectively and stop malicious emails from ending up in employees’ inboxes. That said, Group-IB urges organizations to foster a culture of cybersecurity and educate their employees on how to identify phishing emails. Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence platform led the analysis into Dark Pink, can help organizations shore up their security posture by equipping them with the latest insights into emerging threats.

READ MORE

- Safer Automation: How Sophic and Firmus Succeeded in Malaysia with MDEC’s Support

- Privilege granted, not gained: Intelligent authorization for enhanced infrastructure productivity

- Low-Code produces the Proof-of-Possibilities

- New Wearables Enable Staff to Work Faster and Safer

- Experts weigh in on Oracle’s departure from adland