SANTA CLARA, CA – MAY 10: A sign is posted in front of the Nvidia headquarters on May 10, 2018 in Santa Clara, California. Nvidia Corporation will report first quarter earnings today after the closing bell. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images/AFP (Photo by JUSTIN SULLIVAN / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / Getty Images via AFP)

Are China’s government and military still acquiring Nvidia chips despite the US ban?

- Government and military-affiliated entities from China acquired Nvidia Corp. semiconductors in the past year, circumventing US export bans.

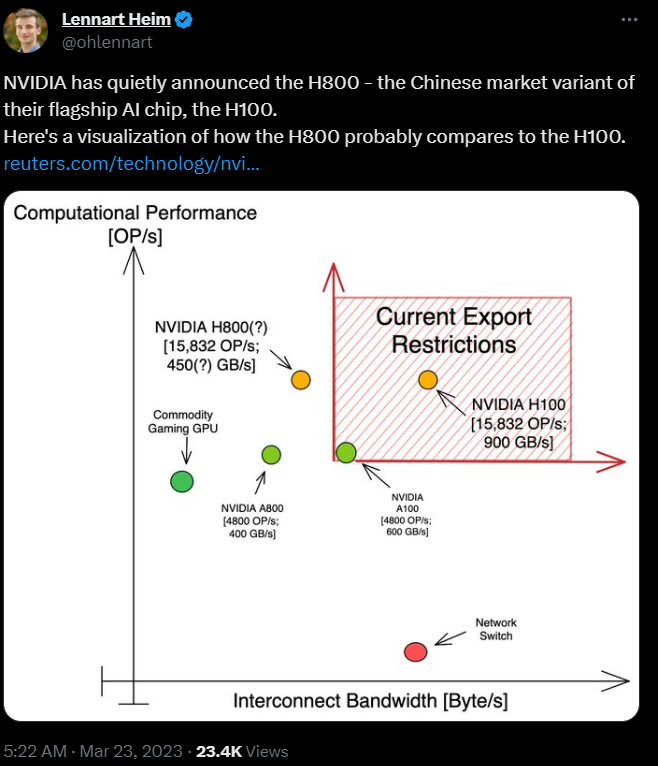

- The report states that Chinese suppliers, primarily unidentified, sold Nvidia’s A100, H100, A800, and H800 chips—affected by US export bans over the past two years.

Amid Huawei’s groundbreaking advancements in 5G technology, the US authorities have intensified efforts to fortify export restrictions, aiming to curtail chip access for Chinese company subsidiaries abroad. In their quest, regulators honed in on semiconductor chips, particularly those crafted by Nvidia for the Chinese market. However, history suggests that those affected by restrictions often seek inventive ways to bypass them. This trend holds even for Nvidia’s clientele in China.

In an intriguing disclosure reported by Reuters, the past year witnessed a covert affair where Chinese military bodies, state-backed AI research hubs, and universities orchestrated a discreet acquisition of prohibited Nvidia semiconductors, barred from export to China. According to the Reuters examination of tender documents, the transactions directed by obscure Chinese suppliers underscore Washington’s persistent challenges.

Despite stringent bans, the US grapples with the intricate task of entirely severing China’s pathway to cutting-edge US chips and tools that could propel advancements in AI and sophisticated military computing. In simple terms, it’s not against the law in China to buy or sell high-end US chips. Therefore, publicly available documents have revealed that numerous entities in China have purchased Nvidia semiconductors even after restrictions were put in place.

For context, Nvidia makes chips called graphic processing units (GPUs), which are known to be much better than other products when handling AI tasks. They can efficiently process large amounts of data required for machine learning. These chips include the A100 and the more powerful H100, which were banned from export to China and Hong Kong in September 2022.

Additionally, the slower A800 and H800 chips, developed by Nvidia specifically for the Chinese market, were also banned last October. The fact that Chinese firms still want and can get these banned Nvidia chips highlights the limited options available to them. Even though companies like Huawei work on alternative products, Nvidia’s GPUs are in high demand. Before the bans, Nvidia had a 90% share of China’s AI chip market.

Source: X.com

Who in China is still buying chips from Nvidia?

Reuters data shows buyers ranged from prestigious universities to entities facing US export restrictions—the Harbin Institute of Technology and the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. These institutions have faced accusations of military involvement or affiliation with a military body against US national interests.

In May, the Harbin Institute of Technology in China acquired six Nvidia A100 chips for training a deep-learning model. In December 2022, the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China purchased one A100, with its intended use remaining undisclosed. “The Reuters review found neither Nvidia nor retailers approved by the company were among the suppliers identified. It was not clear how the suppliers procured their Nvidia chips,” the news agency company noted.

Reuters also noted that numerous government departments submitted more than 100 requests to buy A100 chips, and even after the October ban, there have been dozens of requests for the A800. “Tenders published last month also show Tsinghua University procured two H100 chips while a laboratory run by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology procured one,” it added.

According to military records, there was also a branch of the People’s Liberation Army in Wuxi, Jiangsu province, which sought 3 A100 chips in October and one H100 chip this month. However, details in military records are often blacked out, and Reuters couldn’t find out who won the bids or why they made the purchases.

Most of these requests indicate that the chips are used for AI. However, the amounts purchased are small and insufficient to create a complex AI model from scratch. For instance, to build a model similar to OpenAI’s GPT, you’d need more than 30,000 Nvidia A100 cards, according to research firm TrendForce. Nevertheless, even a few of these chips can handle intricate machine-learning tasks and improve existing AI models.

In one case, the Shandong Artificial Intelligence Institute awarded a contract worth 290,000 yuan (US$40,500) to Shandong Chengxiang Electronic Technology for five A100 chips last month. Many of these contracts specify that the suppliers must deliver and install the products before receiving payment. Most universities also published notices confirming the completion of transactions.

Tsinghua University, often called China’s MIT, has been actively submitting requests and has acquired around 80 A100 chips since the ban in 2022, Reuters noted. In December, Chongqing University sought a new A100 chip through a tender, and the delivery was completed this month, as indicated in a notice.

Jensen Huang, President and CEO of Nvidia Corporation, returns to the hearing room during a US Senate bipartisan Artificial Intelligence (AI) Insight Forum at the US Capitol in Washington, DC, on September 13, 2023. (Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / AFP)

The rise of the underground market amidst US bans

The export control first announced in October 2022 has given rise to an informal underground market in China, with vendors being cautious and aiming to avoid attention from both US and Chinese authorities. After all, the global surge in demand for high-end chips, driven by the widespread success of OpenAI’s ChatGPT and the booming field of AI, led to the skyrocketing need for Nvidia’s microprocessors.

In June last year, Reuters spoke with ten vendors in Hong Kong and mainland China who described being able to procure small numbers of A100s easily. Their information highlighted the intense demand in China for the chips and the relative ease with which Washington’s sanctions can be circumvented for small-batch transactions.

Those vendors, who bought the chips outside the US, were quoting HK$150,000 ($19,150) per card, according to Ivan Lau, co-founder of Hong Kong’s Pantheon Lab, who was then trying to purchase 2-4 new A100 cards to run the startup’s latest AI models. “They told us that there will be no warranty or support.”

In the most recent documents Reuters got hold of, Chinese vendors have said they snatch up excess stock that finds its way to the market after Nvidia ships large quantities to big US firms or import through companies locally incorporated in places such as India, Taiwan, and Singapore.

Responding to the reports, Nvidia states that it follows all the laws related to exporting its products and expects its customers to do the same. A spokesperson for the company mentioned that if they discover a customer has illegally sold their products to others, they will take swift and necessary action. The US Department of Commerce chose not to comment.

Chris Miller, a professor at Tufts University and the author of “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology,” mentioned that expecting the US export restrictions on chips to be foolproof is impractical. He highlighted that since chips are small and easily transportable, making the restrictions completely effective is challenging.

According to Miller, the primary goal is to hinder China’s progress in AI development. By creating obstacles in acquiring large quantities of advanced chips, it becomes more difficult for them to build extensive clusters capable of training sophisticated AI systems.

READ MORE

- Strategies for Democratizing GenAI

- The criticality of endpoint management in cybersecurity and operations

- Ethical AI: The renewed importance of safeguarding data and customer privacy in Generative AI applications

- How Japan balances AI-driven opportunities with cybersecurity needs

- Deploying SASE: Benchmarking your approach