In the thick of the US-China chip war, Beijing may have revived a program halted five years ago to attract top talents. (Photo by SAUL LOEB / AFP)

Chip war: As US tightens curbs, China silently poaches foreign tech talent

- In the thick of the US-China chip war, Beijing may have revived a program halted five years ago, to attract top talents.

- The program is more secretive this time around.

- Qiming focuses on recruiting individuals from scientific and technological fields, including “sensitive” or “classified” sectors such as semiconductors.

For a decade up to 2018, China sought to recruit top foreign-trained scientists and engineers under its Thousand Talents Plan (TTP), which Washington viewed as a threat to US interests. The plan, started in 2008 and halted just before the chip war between the US and China intensified, has recruited thousands of researchers from countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, Singapore, Canada, Japan, France, and Australia.

After ten years, China swept TTP under the rug because the FBI was ramping up its investigation into individuals suspected of serving Chinese interests via the program. Chinese authorities reportedly ordered government mouthpieces to stop promoting the project in September 2018.

According to the Hong Kong Economic Times report, the effort to wipe TTP from public attention based on official documents in the plan’s name should not appear in any public notice. Mentions of the project were also censored on Weibo and other Chinese social media since April 2018. It is as though China is guilty of all that the US has accused Beijing of regarding the TTP program.

Now, five years later, there have been reports indicating that China has resumed enticing expatriate scientists and foreign researchers to relocate to China through its now-revived TTP program, which aims to make the nation a global leader in science and technology.

“Two years after it stopped promoting TTP amid US investigations of scientists, China quietly revived the initiative under a new name and format as part of a broader mission to accelerate its tech proficiency, according to three sources with knowledge of the matter and a Reuters review of over 500 government documents spanning 2019 to 2023,” Reuters stated in a report earlier this week.

Here’s what we know about the original TTP program

When the Chinese Central government unveiled TTP, it was promoted as a scheme to bring leading Chinese scientists, academics, and entrepreneurs living abroad back to China. However, by 2011, the project grew to encompass younger talent and foreign scientists, and a decade later, TTP had attracted more than 7,000 people overall. For Chinese scientists, the scheme gave them a strong financial incentive to return home.

It was an opportunity for foreigners to join the Chinese system with major administrative hurdles removed. Documents found online indicated that the applicant of TTP must already have a firm job offer from a Chinese institution. The scheme was open to Chinese scientists under 55 and foreigners younger than 65. All applicants had to have worked at renowned universities outside China and amassed a strong publication record.

All successful applicants were promised a one million yuan (US$151,000) starting bonus and the opportunity to apply for a research fund of three to five million yuan. Foreign scientists received additional incentives, such as accommodation subsidies, meal allowances, relocation compensation, paid-for visits home, and subsidized education costs. To top it off, employers also had to find jobs for foreign spouses or provide an equivalent local salary.

Then there was the Thousand Youth Talents Plan, that targeted foreign and expat Chinese scientists under 40. Unlike the primary Thousand Talents Plan, Chinese returnees receive the same benefits as foreign recruits under the Thousand Youth Talents Plan.

What will TTP be like in the US-China chip war era?

The race to attract tech talent comes as President Xi Jinping emphasizes China’s need to achieve self-reliance in semiconductors amid a worsening chip war with the US. Source: Shutterstock

Based on information from national and local policy documents and online recruitment advertisements, the primary replacement for TTP is a program called Qiming, which is overseen by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. The revamped recruitment drive, reported in detail by Reuters, offers perks including home-purchase subsidies and typical signing bonuses of three to five million yuan, or US$420,000 to US$700,000.

China’s calling its own – and others – home with strong incentives.

Citing people familiar with the matter, Reuters indicated that the Qiming program recruits from scientific and technological fields that include “sensitive” or “classified” areas, such as semiconductors. “Unlike its predecessor, it does not publicize awardees and is absent from central government websites, which the sources said reflected its sensitivity,” the report reads.

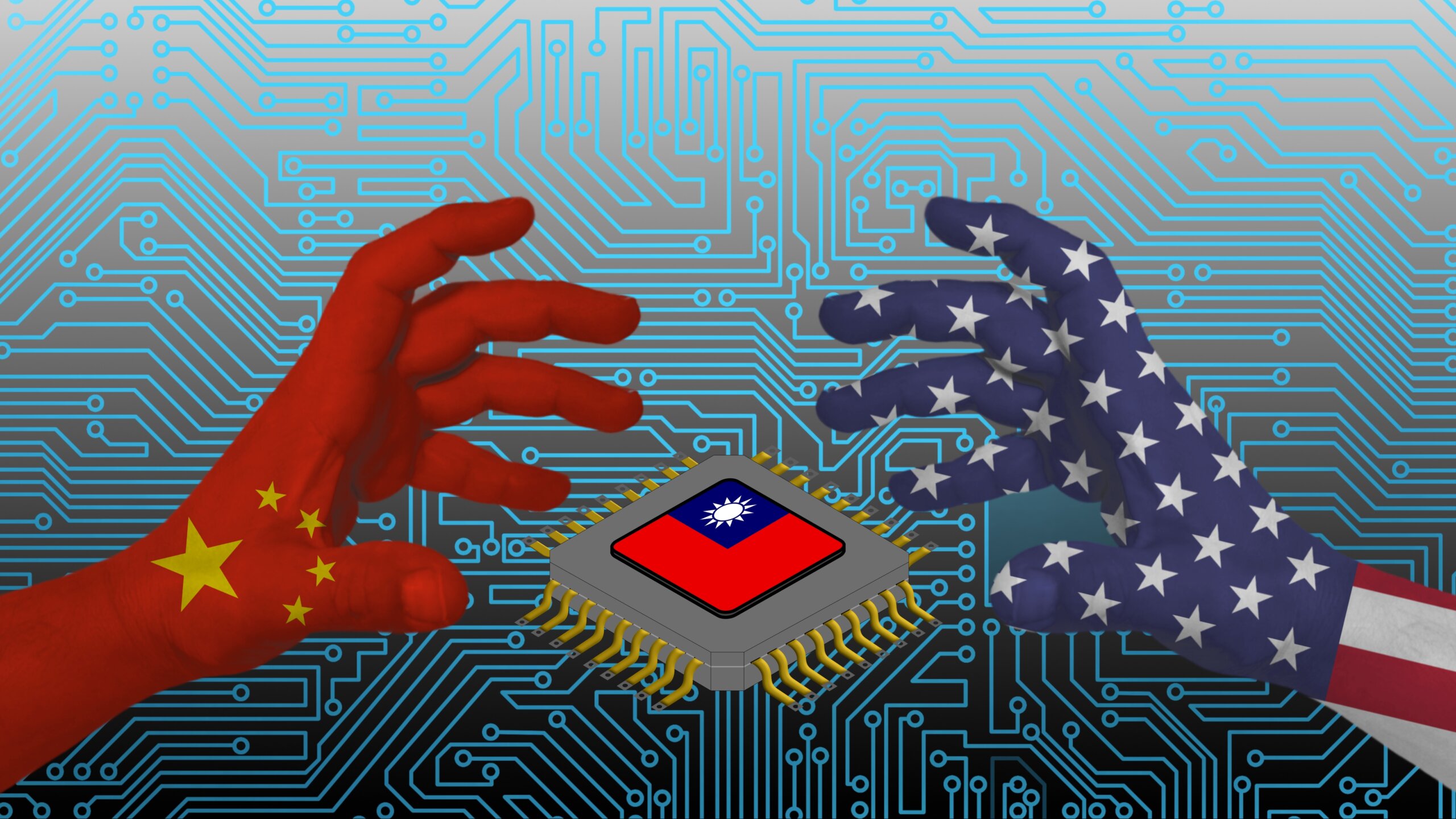

That’s unsurprising considering the race to attract tech talent comes with President Xi Jinping emphasizing China’s need to achieve self-reliance in semiconductors in the face of US export curbs.

Although China’s chip industry has flourished in recent years, the country still faces a shortage of about 200,000 people this year, including engineers and chip designers, according to a 2021 report published by the China Center for Information Industry Development, a government think tank, and the China Semiconductor Industry Association.

“Most of the applicants selected for Qiming have studied at top US universities and have at least one Ph.D.,” Reuters quoted one of the sources, adding that scientists trained at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard, and Stanford universities were among those sought by China.

Could MIT graduates be lured by the new Chinese scheme?

After all, when it comes to technological advancement, the pursuit of skilled talent stands as a cornerstone for progress, and China knows well that if its progress is tied down by the US, there have to be other ways to make up for that slack.

READ MORE

- Safer Automation: How Sophic and Firmus Succeeded in Malaysia with MDEC’s Support

- Privilege granted, not gained: Intelligent authorization for enhanced infrastructure productivity

- Low-Code produces the Proof-of-Possibilities

- New Wearables Enable Staff to Work Faster and Safer

- Experts weigh in on Oracle’s departure from adland